Here is a great video on how some agates form, perhaps most:

—

—

At this point, let me lapse into text from my now dead book project. This is me talking:

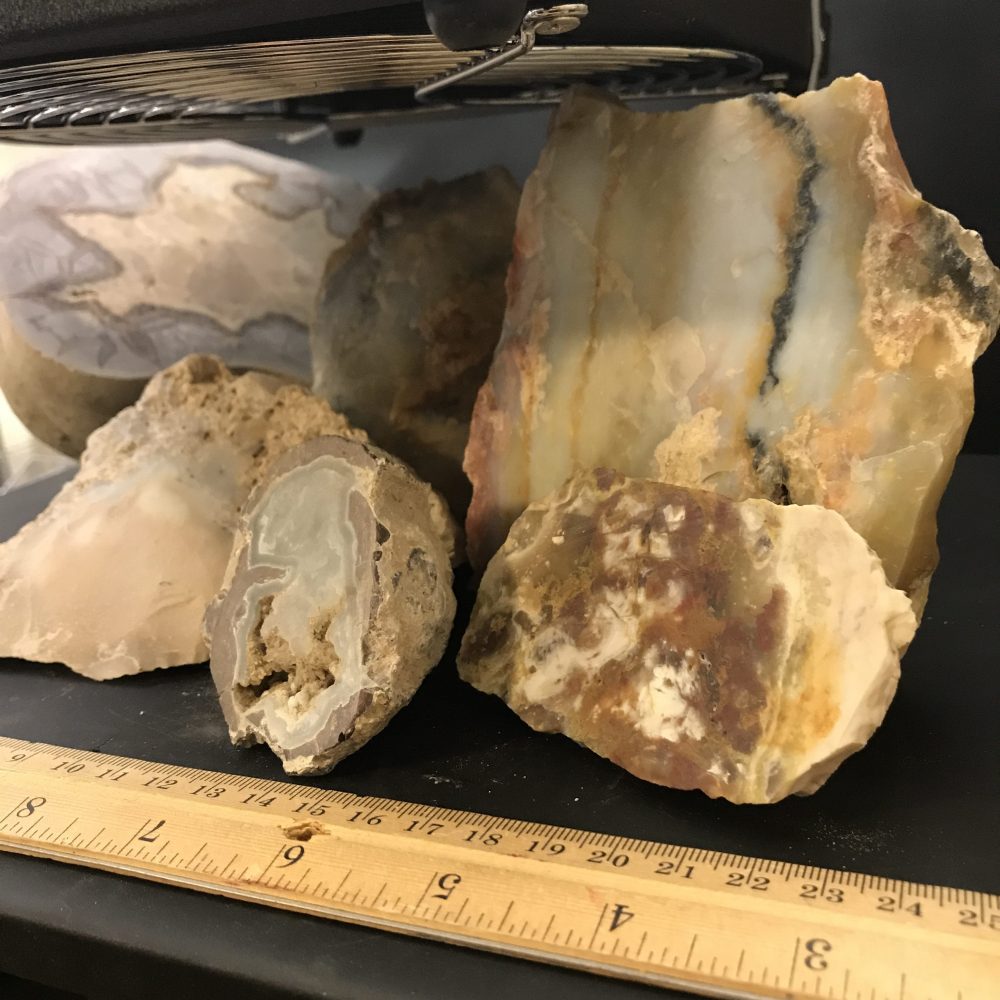

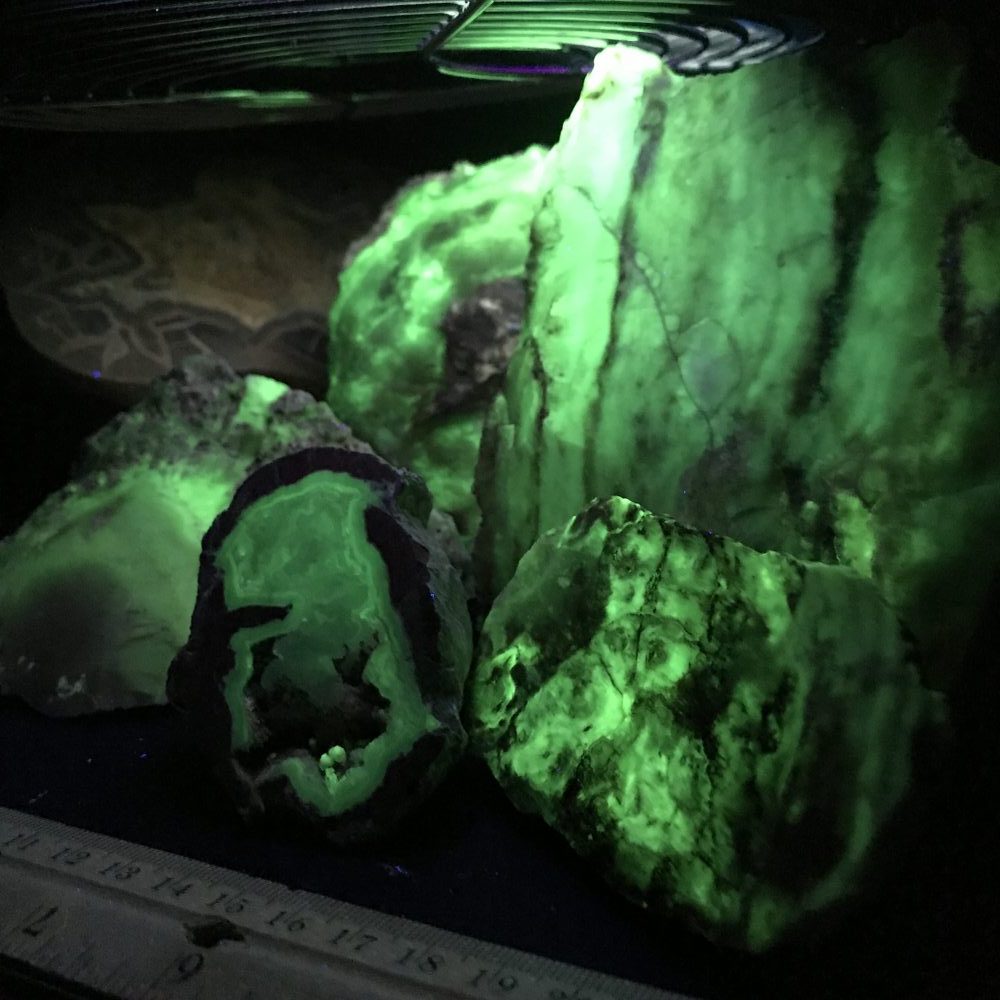

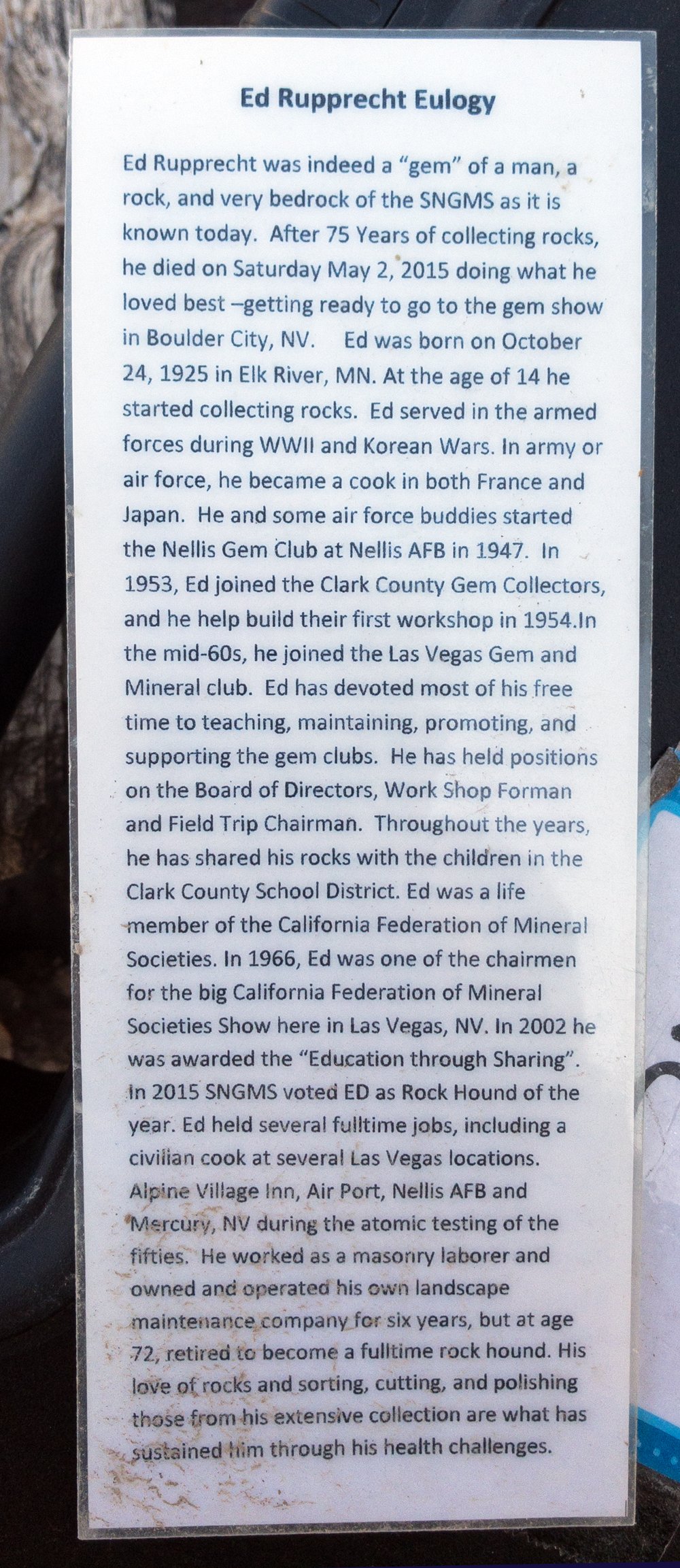

In the case of agates, some literature calls them a, “distinctly banded fibrous chalcedony.” While that may be true for science, a technical discussion on that beyond the scope of this book, agates are simply pretty, translucent at least in part, and common throughout America and the Southwest. I’ve described Burro Creek before. That’s an area in Arizona for collecting. The Cady Mountains in the Mojave Desert near Barstow, California has many kinds of agates, including what’s called the beautiful Top Notch. Clubs may have claims focused on agates, like the one near Las Vegas owned by the Southern Nevada Gem and Mineral Society.

In an interview with Valley Verde TV, Pat McMahan, the world’s leading agate expert, summed up their origin story in just a few unscripted sentences.

“An agate is actually a type of quartz. It’s a non-crystalline quartz and it often forms as a result of volcanic ash like what you have at Mount St. Helens. So, you have a lava flow like you have in Hawaii that has gas pockets and cracks in it — these become the future home of agates. You then have a subsequent eruption with volcanic ash. Rain falls on top of the ash, picking up the silica of the ash, ashes are a form of quartz, depositing that in the lava rock. The rain then soaks through the lava rock, fills the gas pockets, and if it picks up minerals in the process, you have agates that are colored and have inclusions of different kinds. More rain ensues, and ashes are washed away after millions of years, the lava rock turning into soil, with agates just laying there for us.”

Video with Pat explaining geode formation here:

—

—

In explaining petrified wood formation, Halka and Chronic use similar terms. “Because volcanic ash is made of tiny fragments of unstable silica glass, groundwater seeping through the sediments soon becomes charged with dissolved silica. The silica tends to come out of solution when it contacts organic material such as old wood or animal bones. Little by little it has accumulated in pore spaces within the trunks, bringing with it traces of iron, manganese, and other mineral substances that now add brilliant color to the wood.” If we can think of gas pockets and cracks filling with silica instead of replacing pore space within wood, we might better understand the process of agate building.

The first video graphically demonstrates what Halka and Chronic and I could only paint a picture of with words.

—

https://www.instagram.com/tgfarley/

Follow me on Instagram: tgfarley