Group Travel

The benefits of caravanning or driving with a group fall apart if one is left behind. A trip leader may feel pressure to keep a group going to its destination, even if a member breaks down. That driver must then fix the problem themselves, if they can, and then navigate back to pavement. Or, they must get help from the outside. This leads into a discussion about vehicle recovery, communications, and personal survival.

First Things First

Traveling in a caravan off-road is often a high speed race into the wilderness. The group leader, familiar with the road, may blaze ahead with the group struggling to keep up. In so doing, it is nearly impossible to keep track of every turn and fork in the road, especially if one is driving solo. That’s a problem. A real problem. Because if you have to turn back without the group, you may not be able to find your way back. You are guided in, can you guide yourself out?

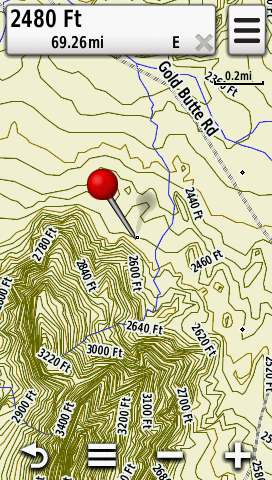

At the very least try to set a waypoint when you leave pavement. I take a photo with my Garmin Montana 650 handheld. It assigns a GPS coordinate to each photo it takes, eliminating manual entry of waypoints. I can later call up the photo and the Garmin will ask if I want to navigate back to that point. Taking more photos along the way at each fork and bend is impossible for me while driving but I will at least have one point I can dead reckon back to.

Communications

With A Cell Phone

Communicating with a road service is no problem if cell phone coverage exists. Even when connected, however, a traditional group like AAA may refuse to dispatch a tow truck down an unmaintained BLM or USFS road. If you are in the Jeep community, a Jeep club member, you will probably have friends and contacts that will come from incredible distances to help. For the rest of us, an off-road recovery service plan is needed, along with a way to get in touch with that towing company without cell phone coverage. A good solution is a satellite messaging device paired with an off-road vehicle recovery plan.

Without a Cell Phone

— Satellite Text Messaging Devices

The SpotX is a satellite text messaging device (internal link). It requires a subscription along with buying the device. Options are personal recovery services and vehicle recovery services. Spot X competes with Garmin inReach products.

SpotX provides personal recovery through GEOS, a worldwide group that facilitates search and rescue. With the GEOS option subscribed to, a rockhound can summon help through the SpotX by simply pushing the device’s dedicated SOS button. GPS coordinates are automatically sent with any SOS message.

This service is keyed to the subscriber but is unthinkable an emergency team would refuse aid to anyone in a life-threatening situation. That person, though, will probably have to pay the cost of this uncovered rescue. GEOS stand-alone plans are available for individuals, no device needed. Many backpackers use GEOS while wilderness traveling. Garmin’s inReach products also offer GEOS.

A vehicle option is the S.O.V. or Save Our Vehicle service. This summons a company called Nation Safe Drivers to recover or make road worthy any broken down or bogged vehicle. That includes SUVs, ATVs, or motorcycles. Unlike AAA, this service is tied to a particular vehicle. Nation Safe promises that their partners will recover a vehicle on any kind of road regardless of location. That said, towing services are far and few between in the rural southwest and a rockhound should be prepared to wait a very long time for recovery.

Search and Rescue teams are frequently summoned to help people stranded in the wilderness due to vehicle breakdowns. This is a terrible use of trained, needed people. A rockhound or prospector should have a vehicle recovery plan, use that, and only if no assistance is available, then ask SAR for help.

This writer has both SpotX options and has had the good luck not to need them. Yet.

The SpotX is challenging to set up. The device requires a Mac or Windows desktop or laptop machine to first configure the device and then for later updates and changes. You can’t use a mobile OS to set up the SpotX but a phone app provides some features after the device has been configured with a non-mobile OS.

Download the SpotX program, enter the required information, sync the SpotX to a desktop or a laptop over a cable. When updating the device, download the latest updater program first, run that, and then again sync the device over cable. Check for updates before going into the field as the device may not work without the latest software.

The SpotX operates best when stationary and with a clear view of the sky. Run several test messages before going out. Text messages are delivered more quickly and more dependably than e-mail messages. Coordinates can be sent with every message. The keyboard is frustrating to use with its tiny keys. Really frustrating.

-A Satellite Phone

Satellite phones provide direct voice communications. One still needs a personal and vehicle recovery plan, of course, after connecting to the terrestrial telephone network. Sat phones themselves are reasonably priced but air time is phenomenally expensive. They can be rented for short periods but air time will still cost dearly.

-Amateur Radio

Ham radio is excellent for emergencies when other services fail. Coverage is likely over much of the Southwest with what are called repeaters, small radio stations that are on the tops of the most remote and unlikely mountains and even on the roofs of casinos. Emergency traffic is relayed between a ham with a telephone connection and a person in the field seeking help. If a repeater has an accessible autopatch feature then things proceed more smoothly.

Ideally, the caller initiating the emergency call must have an amateur radio license, obtained by passing an FCC test. In reality, anyone in a life or death situation will be listened to, in fact, most of the nearby ham community will likely tune in when another ham declares an emergency. All other traffic will then get voluntarilly suspended from the particular channel being used. A Technician class license takes 15 to 20 hours of study to prepare. All manner of people and resources will assist a future ham with passing. I hold a General Class license, my call sign is KD6NSP.

-FRS/GMRS

The Family Radio Service or FRS is normally used to communicate between vehicles or between people on a hike. A walled garden system, FRS cannot be depended on to communicate with the outside world. GMRS or General Mobile Radio Service transmits further and, in some areas, employs a network of repeaters to get messages through. GMRS requires an FCC license but no testing. Of the two, GMRS offers the best chance for getting help.

-Citizen’s Band Radio

C.B. is still with us although less so. On a hill or in open country, a five-watt C.B. radio signal can travel a fair distance. Channel 9 is supposed to be used in emergencies, although Channel 19 has the most traffic. C.B. allows a chance of communicating with the outside world. Find a C.B. shop near truck stops or travel plazas to professionally install a unit. Installers can tweak a radio for better performance if asked discretely. Handhelds are nearly worthless. A vehicle mounted C.B. radio is not that expensive, except for so called SSB units which are very desireable. As with everything radio, the magic is in the antenna.

First aid

Pre-made first aid kits come in many styles which all need modifying. Every kit lacks an inadequate number and variety of bandages. Bring more, big ones. Cuts in the field are much worse than those in the city. A bigger bandage can be cut to size by sharp, sturdy scissors that must be in every kit. Canvas backed bandages stick, plastic doesn’t. Secure plastic bandages with tape if nothing else is available.

Mandatory bandages are knuckle bandages and wound closure strips. Knuckle bandages look like an “H”, with four finger-like strips extending from a central square. They conform to nearly every cut and can be bought at all well stocked pharmacies. Purchase knuckle bandages for home, the truck, the field. Buy bandages in quantity as they need frequent changing. Consider partially unwrapping bandages before a trip. Especially with a finger cut, opening a bandage package and removing the backing is extremely difficult while bleeding.

Wound closure strips are essential. These are called butterfly closures or steri-strips. These bandages, a series of fabric tabs, attempt to bring the two sides of a shallow wound together. Normal bandages, by comparison, simply cover a wound. Any injury requiring butterfly closures should be looked at as soon as possible by a medical professional.

Bandage tape is essential, the better to keep a big bandage secure after applying it over a wound. Such tape can wrap toes prone to blistering before hiking. Bring nail clippers or scissors to trim toe nails which can bother or go bloody on a long downhill.

Sore or blistering feet must be addressed immediately, even when a large group wants to move on. A sock change may eliminate a hot spot, in other cases baby powder may help. If a hot spot does develop, cover it with a bandage or mole skin, even duct tape if nothing else. Too often a newcomer lets a foot problem get serious, not wanting to slow their fellow travelers. The result, further injury, bloody socks, discouragement and perhaps impairment.

Antiseptic swabs are good as well as a hemostat, a lightweight surgical plier. These or conventional needle-nose pliers help pull out thorns. A snakebite kit is of dubious merit, especially the old-fashioned ones that require self-surgery. Noted herpetologist W.C. Fields advised people to always carry a flagon of whiskey in case of snakebite. And to always carry a small snake.

Most importantly, carry all items in a waterproof case or at the very least in double wrapped Zip-Lock bags. Water always finds a first aid kit. Always. Kayakers and rafters use waterproof cases and these are good. Throw a few matchbooks in any first aid kit. Someone will need them.

Some of my kit

Survival at a vehicle is usually assured provided adequate water and food exists. As they should since the rockhound went out for the day or overnight to collect. Less assured is the situation when the rockhound is away from the vehicle and disoriented. Desert washes confuse easily as they meander back and forth, don’t look the same going as they did coming, and provide no elevation to get one’s bearings. Heavily wooded areas confuse with a lack of landmarks and spotty GPS coverage.

Let’s discuss being lost.

Self-Recovery And Survival

Summoning aid over radio was discussed under Communications Section. Navigating with GPS devices and by hardcopy maps were discussed under the Map and GPS Essentials Chapter.

We assume here that the rockhound is unable find a way back to the vehicle. A GPS device has failed, a hardcopy map has gone missing, water is running low, night is approaching. If separated from a group, use a whistle to blow three times in a row. Do this often.

If there is a group, a fellow member will be known as lost rather quickly. People will often wait at their vehicles overnight for a hiker to appear before calling in search and rescue. They will repeatedly honk every vehicle’s horn. Listen for that. Know that people are waiting and that more are coming.

If there is no group, at least a vehicle is on a road. Correct? Unless no one was notified of the prospectors’ trip, a bad thing indeed, search and rescue will be gathering soon. Within a full day, certainly two, probably assembling at the vehicle. A vehicle is far easier to find than a person and that is what they will locate first.

Settle in for an uncomfortable night of little sleep. Fight panic. The situation is not out of control. A rockhound is still within walking distance of a vehicle, perhaps not too far, as most of us carry heavy tools or rocks. Night travel needs thought. One misstep may produce a twisted ankle, pain, incapacity. Cactus are everywhere in the desert, as well as mesquite, which will savagely wound on a brush-by. Save energy for the next day. Hang on.

With dawn, try to get oriented again. Look at the sun and the mountains; try to picture where the vehicle is. If totally confused, it may be best to stay in place, rather than flounder through brush and cactus or go further down a wash or canyon. If one decides to move, leave a litter trail behind and start breaking branches now and then, giving the SAR team clues.

If in the mountains, never loose elevation unnecessarily. In theory, a mountain stream will eventually lead one back to more level ground and then recovery. In reality, many streams are absolutely choked with vegetation, making even walking downhill difficult as one thrashes through brush and over large, uneven boulders.

It is a new, unsettling and distressing experience to be lost and without water. More effort creates a desire for water one doesn’t have. Another argument for staying in place. People will be coming. Some SAR groups have aircraft support. Make a signal for them. Seek any shade. Sit. Think on better times.

Not Getting Lost

1. Carry a good map and know how to use it. An old-fashioned compass is lightweight, takes up little room in a pack and almost always works. They are best used with a hardcopy map to get oriented to one’s surroundings. Navigating by compass alone means taking a bearing at the trailhead and that takes instruction and practice. Without setting a bearing, the compass may turn useless when trying to return.

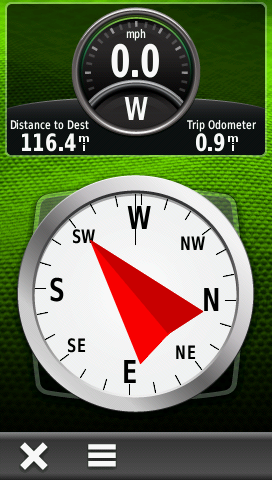

2. Take a GPS device when walking a good distance from a vehicle. Record way points from leaving the vehicle on. Handhelds like the Garmin Montana enable breadcrumbing, allowing the retracing of a path. For GPS units with cameras, a set of photographs will provide a set of effortlessly recorded waypoints. These devices create actionable photographs, assigning coordinates to each image, allowing navigating to any photographed location by simply pressing “Go.”

3. Note prominent landmarks while prospecting, especially power lines, fences, and other man-made objects. A trail never looks the same going in as coming back. Look backwards from time to time. If you get uneasy about navigating back, claw an arrow in the dirt with your boot at trail junctions. Or set a group of rocks at a fork to indicate the way back. In densely wooded areas of the California foothills, I have tied yellow survey tape from Home Depot to trees and shrubs every few hundred yards to lead back to a trailhead. It is easily removed upon return.

4. Carry more water. Food is important but water more so. Lack of water directly impacts strength. More water.

5. Think about a survival plan before any upcoming trip.

6. Remember that whistle. Blow three times in a row each time. A good whistle is heard from a decent distance.

6. As common sense dictates, always tell someone about any off-pavement plans. Provide a trip leader’s telephone number to your friend as well.

—-

Follow me on Instagram: tgfarley

https://www.instagram.com/tgfarley/