Explanation

This draft is from my now dead book project. The images were not intended to violate copyright but to guide my publisher in making new ones. My ex-publisher.

The term geological province isn’t favored anymore, instead, scientists like physiographic or something similarly stilted. I don’t.

Scientists disagree on the borders, names, and numbers of provinces within a state or region. I won’t settle their arguments here.

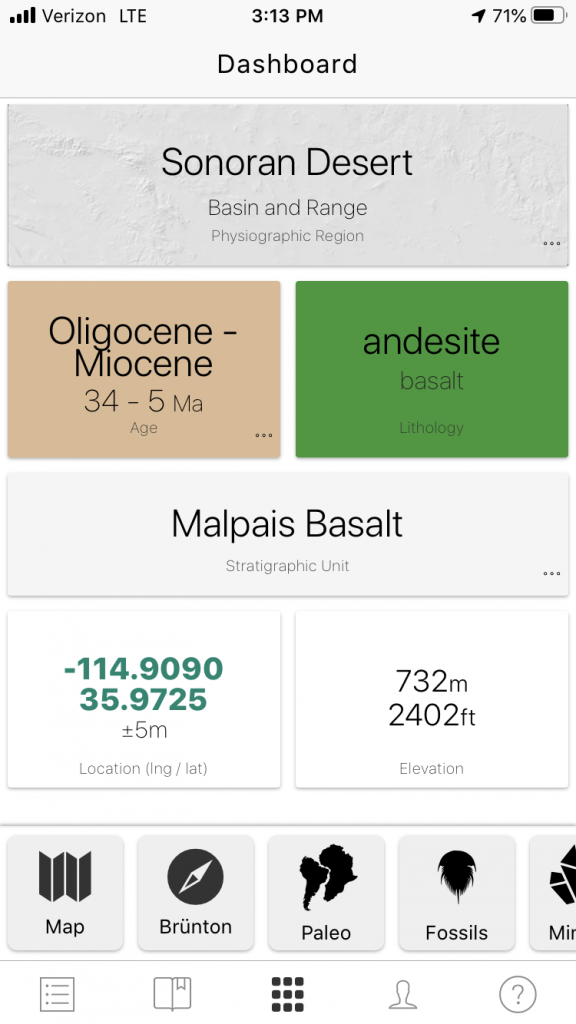

Macrostrat.org’s interactive map tells you what province your area of interest is in. Their free smartphone app gives you a province name for any ground you are standing on in the field. Provided you have cell phone coverage.

I Geological Provinces of The Southwest — The Lay of the Land

The American Geological Institute defines a geologic province as a large region characterized by similar geologic history and development. [Robert Bates and Julia Jackson. Dictionary of Geological Terms (New York: The American Geological Institute, 1984), 207] These characteristics include landforms, natural features of the earth’s surface, rock types, or a shared evolutionary history. Every part of the Southwest belongs to a distinct province with particular landforms and geology.

Geologic provinces show well on maps but are often hard to tell in person. No colors or lines on the ground mark one region from the other. Earth scientists may disagree where boundaries lie. Plants are sometimes better indicators than rocks. Saguaro cactus herald arrival in the Sonoran Desert. A lessening of creosote bush and an increase in sagebrush marks the beginning of the Great Basin Desert. Maps, guidebooks and a little study make these provinces stand out.

II Arizona

Arizona is the sixth largest state in America. It covers 113,909 square miles. New York, Indiana, and Maryland could easily fit inside Arizona’s borders. The state is landlocked, although the Colorado River flows through Arizona to the Pacific Ocean. The state has three distinct topographical areas.

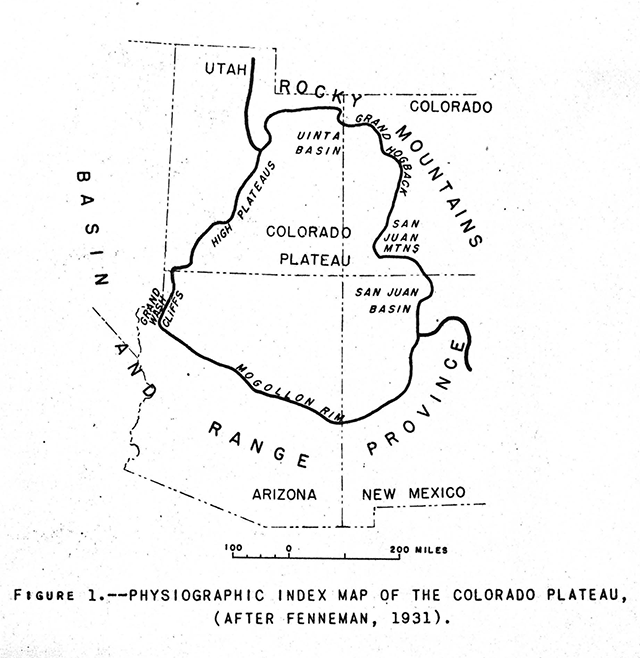

-The Colorado Plateau

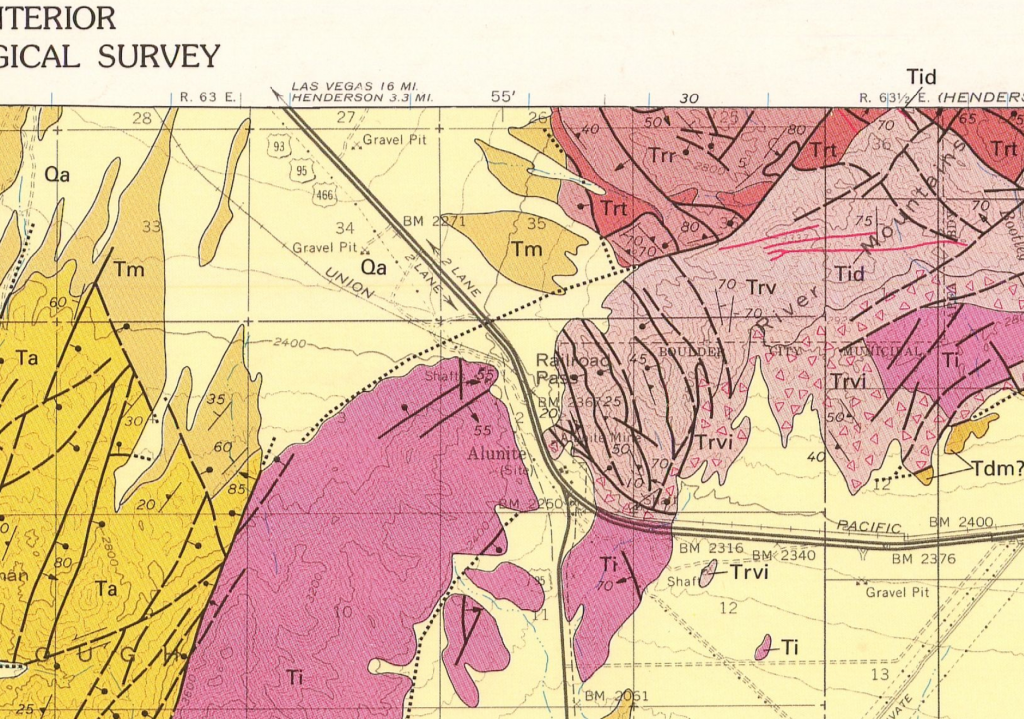

The Colorado Plateau in Arizona runs diagonally northwest southeast through the upper half of the state. Sometimes referred to as the Colorado Plateau Province, this lifted topographical feature extends into Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico. The Plateau may be pictured as centered over the Four Corners of the United States. Its elevation is between 5,000 and 7,000 feet and it covers some 240,000 square miles. [“Colorado Plateau Province” https://www.nps.gov/articles/coloradoplateaus.htm Accessed 08/08/2023]

Any map depicting gold, silver, or copper deposits in the Western United States shows a lack of these minerals in the plateau. That’s because, as Jim Straight puts it, “Both the Columbia and Colorado Plateau are capped with non-metalliferous basaltic flows.” [Straight, Jim. Advanced Prospecting for Hardrock Gold 4th edition (Rialto, California: Jim Straight, 1998) plate No. 1] In other words, ancient lava flows not enriched with precious-metal bearing minerals. This can include non-metal bearing minerals as well, such as fluorite. This holds true for each portion of the four states in the Colorado Plateau.

(The Colorado Plateau across four states)

Arizona’s largest city in The Plateau is Flagstaff. The Hualapai, Navajo and Hopi are among tribes with reservations on this land. The Plateau features much of Monument Valley, the background for many famous John Ford films. The four thousand food wide Meteor Crater lies a short distance from Winslow. In addition, the Grand Canyon wends through the Plateau. Precipitation averages 10 inches annually. Native grasses and scrub cover much of the Plateau, leaving it suitable for grazing. Junipers and pinion trees occupy higher elevations.

-The Transition Zone

Arizona’s Transition Zone or Highlands also runs diagonally in a southeast to northwest fashion, occupying the middle of the state. It is a narrow, mountainous region with many peaks between 9,000 and 12,000 feet. Annual mountain precipitation averages between 20 and 25 inches. This belt separates the northern plateau from the southern deserts. The largest city here is Prescott at 5,368 feet. Numerous Wilderness Areas exist in the Transition Zone along with several National Forests, state park land and a National Monument.

The notable Mogollon Rim divides the Colorado Plateau and the Highlands as it strikes across the entire state of Arizona. This long cliff does not always present itself clearly, but at times it looms 2,000 feet above lower ground like the Tonto Basin. It also plays a part as a weather maker as explained in my weather chapter.

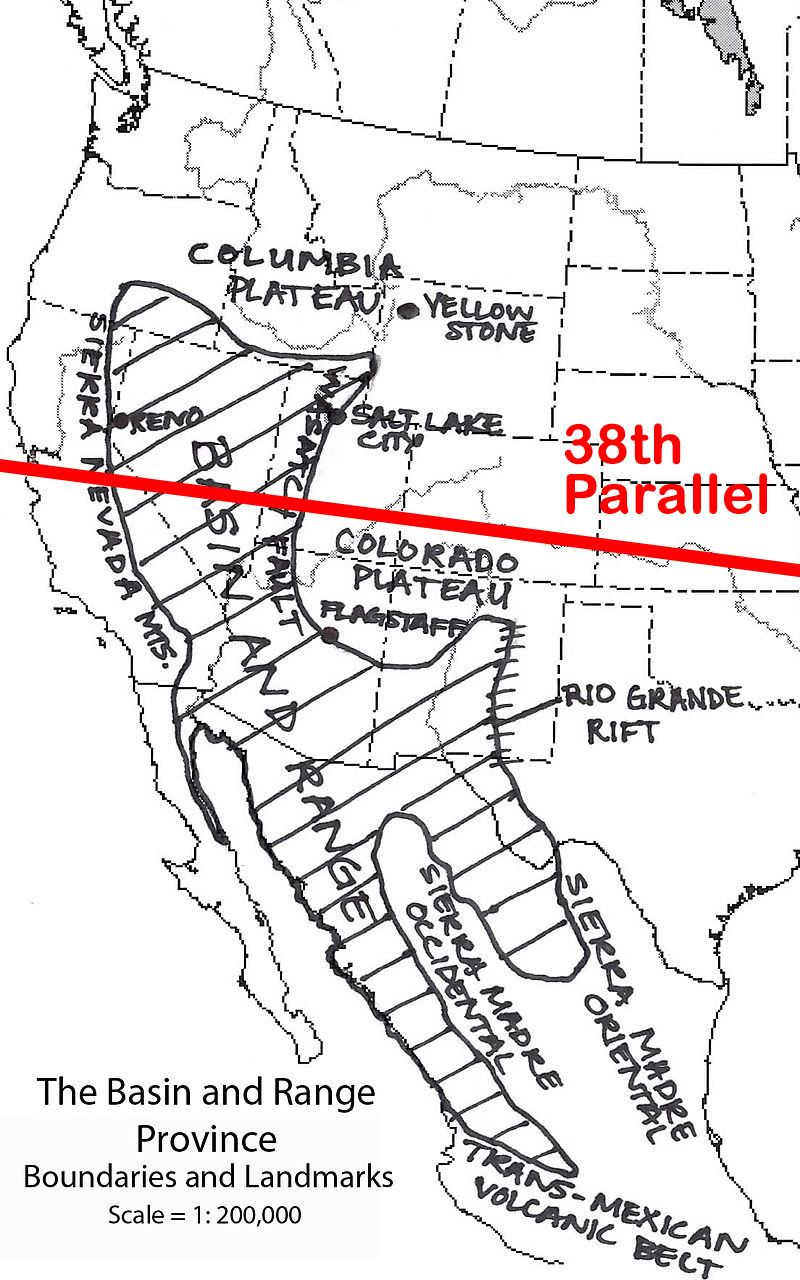

-Basin and Range

The Basin and Range geographic province reaches across vast areas of the Southwest, especially to Nevada. In Arizona, Basin and Range extends across the lower third of the state, dominated by the Sonoran Desert. Most motorists see Basin and Range as an unceasing crossing of low mountain Ranges and desert valleys. The National Park Service, however, is relentlessly positive. As they once put it, “The Basin and Range province has a characteristic topography that is familiar to anyone who is lucky enough to venture across it. Steep climbs up elongate mountain Ranges alternate with long treks across flat, dry deserts, over and over and over again!” [“Geoscience Concepts” NPS. Language now removed.

https://www.nature.nps.gov/geology/education/concepts/concepts_basinrange.cfm]

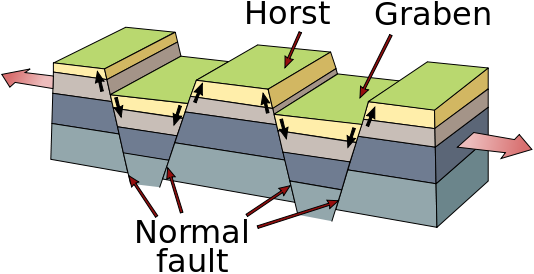

Besides the name Basin and Range, these alternating peaks and valleys are also called horst and graben. These two elements make up a particular rift landscape. Horst and graben occurs when the earth’s crust is stretched up to 100% of its original size. This stretching does not go smoothly. Instead of producing a flat plain when stretched, blocks of the earth’s crust are pulled up and down. Horst and graben creates blocks of the earth’s crust and upper mantle uplifted at angles. These uplifted angles represent fault lines which underlie the topography of Basin and Range.

Within Arizona’s Basin and Range Province lies the Sonoran Desert. It is a complex of low mountain ranges and desert valleys, with annual rainfall of three to four inches. This country is normally no higher than 500 to 2,000 feet in elevation. Basin and Range here is an extension of the Sonoran Desert of Mexico. Arizona’s other desert is the Chihuahuan. It, too, originates within Mexico, although Arizona’s portion wanders in from New Mexico, intruding only into the southeast corner of the copper state. It is in this arid and alternating geologic province of Basin and Range that Arizona’s major cities lie. Kingman, Phoenix, Yuma and Tucson are all denizens of the desert.

(Arizona’s geologic provinces)

III California

-Introduction

For this book, the Southwest reaches to the Pacific Ocean. California deserts feature great rockhounding areas and must be recognized. Extending the Southwest to the Pacific also allows San Diego County to be included, the center of tourmaline mining in the greater Southwest.

-The Mojave Desert

This is the land of the Joshua Tree, as much as the Sonoran Desert is the land of the Saguaro. The two rarely intergrade, each keeping itself to one side of the Colorado River. The Mojave is home to Death Valley, which at one point lies 276 feet below sea level. Death Valley and the Mojave Desert are the hottest and driest parts of California. Rainfall sometimes measures under two inches a year. Lower than the Great Basin, elevations average between 3,500 and 4,000 feet. Californians call this the High Desert.

-The Colorado Desert

The Colorado Desert is a smaller part of the much larger Sonoran Desert. The Colorado covers approximately 7 million acres. It is dominated by the off-limits Chocolate Mountains, over which the military has an aerial gunnery Range. The desert encompasses Imperial County and reaches into the counties of San Diego, Riverside, and part of San Bernardino. The Salton Sea lies on its west side, Bombay Beach its central hamlet. Most of the Colorado sits below 1,000 feet, with below sea level elevations at the Salton Sea.

-Basin and Range including The Great Basin Desert

High, dry, and often cold, the Great Basin Desert reaches from California’s eastern border to touch Oregon and Idaho, most of Nevada, and a significant part of Utah. Elevations range from 4,000 to over 14,000 feet in the White Mountains and the eastern Sierra Nevada. The long-lived Bristlecone pine hangs to life in its montane setting while common sagebrush populates the lowlands below. No water from the Great Basin Desert runs to the sea. At the limit of the Southwest, Bishop, California at 4,150 feet represents the largest California city within the Basin.

-The Peninsular Ranges

“The Peninsular Ranges geomorphic province consists of a series of mountain Ranges separated by long valleys, formed from faults branching from the San Andreas Fault.” So states the California State Park System. [Geological Gems of California State Parks – GeoGem Note 46 -Peninsular Ranges Geomorphic Province https://www.parks.ca.gov/pages/734/files/GeoGem%20Note%2046%20Peninsular%20Ranges%20Geomorphic%20Province.pdf Accessed 08/04/2023] From a political boundary sense, the Peninsular Ranges originate at the Mexican border where both the United States and San Diego County begin. More accurately, though, the Peninsular Ranges extends south across the border to form the backbone of Baja California.

-The Transverse Ranges

The USGS states, “The Transverse Ranges Province of southern California is so-named because the mountains, valleys, and geologic structures within this province lie east-west or ‘transverse to’ the prevailingly northwest-trending grain characteristic of southern California.” [“Geologic Setting of the Transverse Ranges Province” https://geomaps.wr.usgs.gov/archive/socal/geology/transverse_ranges/index.html Accessed 08/06/2023] They also say that two other provinces of southern and central California trend northwest. Basin and Range in Nevada and New Mexico also trends in the same direction.

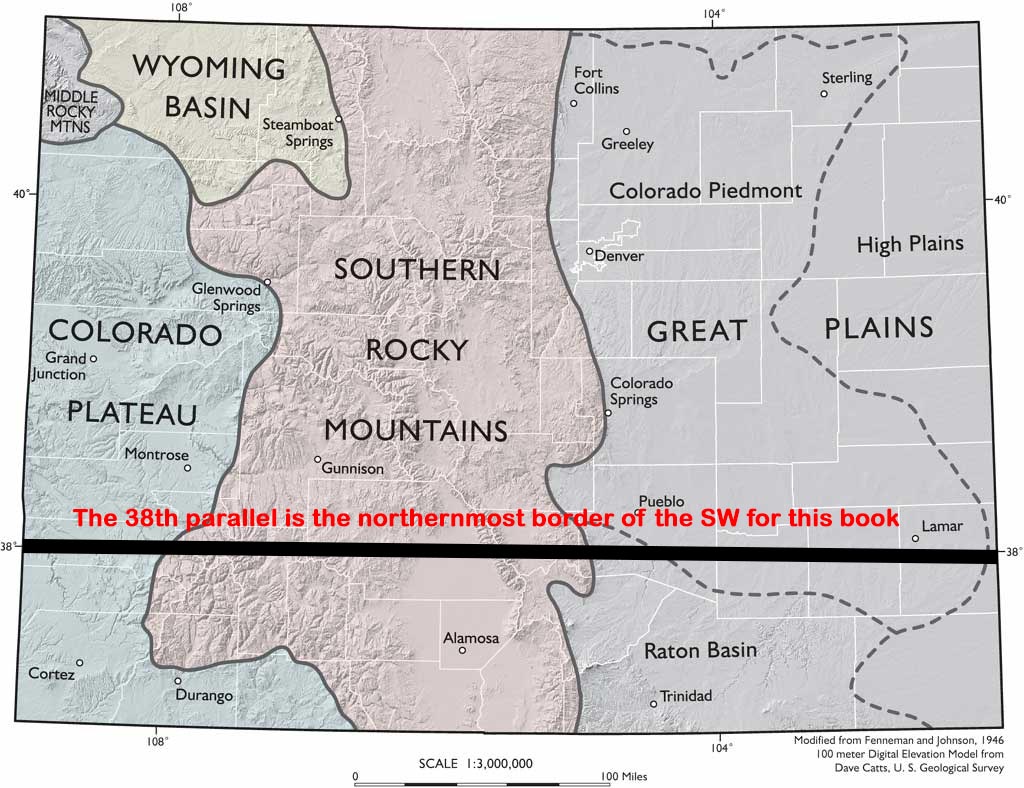

IV Southern Colorado

-Introduction

This book treats the southernmost portion of Colorado, at the northern edge of the Southwest. Major cities are Creede at 8,838 feet and Durango, at 6,523 feet. These high elevations mean a true four-season climate, compared to the two-season climate most of the Southwest enjoys. Snow can fall in October in Creede, with 71 days of snow each year. Snow falls later in Durango.

-Colorado Plateau

Colorado’s western portion of the Plateau includes these National Monuments: Canyons of the Ancients, Yucca House, and Chimney Rock. Western Colorado is uranium country. Most occurrences, though, exist north of this book’s Southwest border. Southern Colorado rock collecting sites are many and for varied materials Richard Pearl describes Colorado as more mineralized than any other state except California.

-Great Plains

The High or Great Plains province covers eastern Colorado. Elevations reach 6,000 feet in this mesa-like area. The High Plains are a part of a larger plains system called the Great Plains. That ranges through southeastern Wyoming, southwestern South Dakota, western Nebraska, eastern Colorado, western Kansas, eastern New Mexico, western Oklahoma, and south of the Texas Panhandle. Essentially, the eastern side of the Rockies.

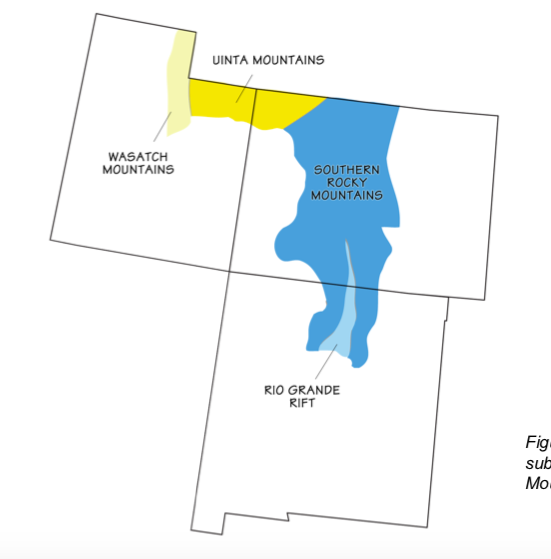

-Southern Rocky Mountains

The Southern Rocky Mountains Province in Colorado continues to New Mexico. Wedged in the lower middle of this province is the Rio Grande Rift Province. It also continues to New Mexico, the Rio Grande River accompanying it. Alamosa is the chief city here at 7,543 feet, the prominent geologic feature the broad San Luis Valley. This valley approaches the size of Connecticut. It is 125 miles long and 65 miles wide, its mean elevation 7,000 feet. Though the country is a semi-arid plain, surface and subsurface water from the Rockies allows a thriving farming community as well as sourcing the Rio Grande.

(Geologic map of Colorado showing Rio Grande Rift)

(Geologic map of Colorado, not showing the Rio Grande Rift)

V Southern Nevada

-Introduction

Nevada is Basin and Range country, north-south trending mountain ranges fixed in parallel fashion across the state. This Basin and Range landform runs from Oregon to Mexico, capturing all of Nevada with it. The Great Basin, as it is known when referring to its entirety, consists of 160 mountain Ranges and 90 Basins.

-Basin and Range

Mountain ranges march unceasingly across Nevada, accompanied by many Basins or low-lying areas. This is not a violent landscape and the motorist driving east-west will little notice. To the rockhound, however, each new mountain Range presents new road cuts and interest heightens each time a Basin’s floor is left behind.

Nevada’s mean elevation is 5,500 feet. This produces a high, dry, mostly cold desert, reflecting the same condition this landform brings to parts of southern California. For Las Vegas, the chief city of southern Nevada, rain is a scant four inches a year, with summer temperatures often exceeding 105 degrees. Nevada is the driest state in America. It averages only nine and a half inches of rainfall a year.

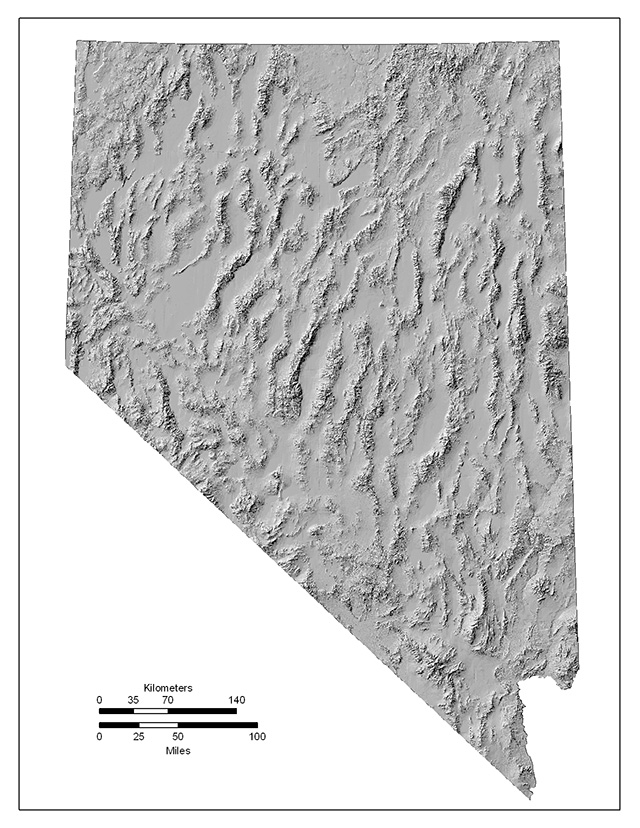

(Southern Nevada, not showing Arizona’s Transition Zone)

(Nevada’s many basin and ranges.: http://crack.seismo.unr.edu/graphics/Maps/nv-topo.jpg)

VI New Mexico

-Introduction

New Mexico is the fifth largest state by area in the United States. It totals 121,412 square miles. The federal government owns 35% of that territory. 14,062 square miles is in National Forest and approximately 20,312 square miles in BLM lands. New Mexico’s twenty-three Indian tribes own or control 5,739 square miles.

The state’s topography is varied and dramatic. Scenic gorges, mesas, high plateaus, canyons, valleys, and dry washes or arroyos are all part of New Mexico. Average elevation is about 4,700 feet. The lowest point is just above the Red Bluff Reservoir at 2,817 feet where the Pecos River flows into Texas. The highest point is Wheeler Peak at 13,161 feet. 23 Indian tribes exist in New Mexico. That includes nineteen Pueblos, three Apache tribes (the Fort Sill Apache Tribe, the Jicarilla Apache Nation and the Mescalero Apache Tribe), and the Navajo Nation.

(New Mexico geological provinces)

-The Southern Rocky Mountain Province

The Southern Rocky Mountain province is by definition mountainous ground considered part of the Southern Rocky Mountains. The Sangre de Cristo Mountains, the Tusas Mountains, and the Sierra Nacimiento are included in this grouping. They lie on either side of the Rio Grande Rift Province.

The southern end of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains terminates near Santa Fe; this mountain Range marks the western edge of the Great Plains. The Range continues northward for some 200 miles until Salida, Colorado. Herbert Ungnade wrote that, “The Sangre de Cristo Mountains were hunting grounds for Apache and Comanche Indians and that the Spaniards ventured into them only in heavily armed groups.”

The Southern Rocky Mountain Province contains some of the highest peaks in New Mexico. Like the aforementioned 13,000-foot Wheeler Peak. Lower country exists as well. Like the Questa Caldera in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains northeast of Taos. Calderas are ancient basin shaped volcanic depressions, collapsed volcanoes, and this one sits at approximately 7,400 feet. Of special note is the ancient Valles Caldera National Preserve near Bandiler. Looking deceivingly like a flat grassy field, the caldera is actually a thirteen-mile wide depression supporting meadows, wildlife and wandering streams. Bandelier National Monument and Pecos National Historical Park nearly align on the same geographic parallel. They two points effectively serve as the southernmost reach of the Southern Rocky Mountains Province.

(The Southern Rocky Mountain Province, not showing the Rio Grande Rift Province which is in the middle, following the Rio Grande River.)

-The Colorado Plateau

The Colorado Plateau in New Mexico lies in the upper northwest corner of the state. New Mexico’s two major cities, Santa Fe and Albuquerque, lie on the edge of its borders. Their elevations are 7,199 feet and 5,312 feet, respectively. As noted in the description of Arizona and Colorado, the Colorado Plateau Province’s 130,000 square miles is lodged squarely over parts of the Four Corners States. The Navajo Nation also owns much territory in the Colorado Plateau of New Mexico. They in fact own 27,000 square miles in the Four Corners region, an area larger than West Virginia. The rich topography of the plateau partly explains the nine National Parks and eighteen National Monuments located there.

(New Mexico’s density of parks)

-The Rio Grande Rift Province

The Rio Grande Rift Province splits New Mexico in two, with the Rio Grande River running down the middle. The rift begins high in the Colorado Rocky Mountains near Leadville, Colorado. It terminates in the Mexican State of Chihuahua close to Ciudad Juárez. Its stateside length is over 600 miles. The rift is not a valley or canyon caused by erosion from the Rio Grande River. Instead, the zone is a tearing down and building up of the earth’s crust. The Colorado Plateau pulls to the west, the High Plains to the east. This action is from two parallel fault zones that run north-south through New Mexico.

(New Mexico’s Rio Grande Rift Province)

-Basin and Range Province

Basin and Range topography in New Mexico occupies the lower southwest portion of the State. This same geologic occurrence extends from Mexico to Canada. [Christiansen, Eric and Kenneth Hamblin. Dynamic Earth: An Introduction to Physical Geology (Burlington, Massachusetts: Jones & Bartlett Learning. 2015) 592 ] Southern Arizona, eastern California, southern Idaho, western Utah, and most of Nevada. Again, Basin and Range is marked by mountain Ranges striking in a northerly to northwest fashion, alternating with wide Basins.

(New Mexico’s Basin and Range Province)

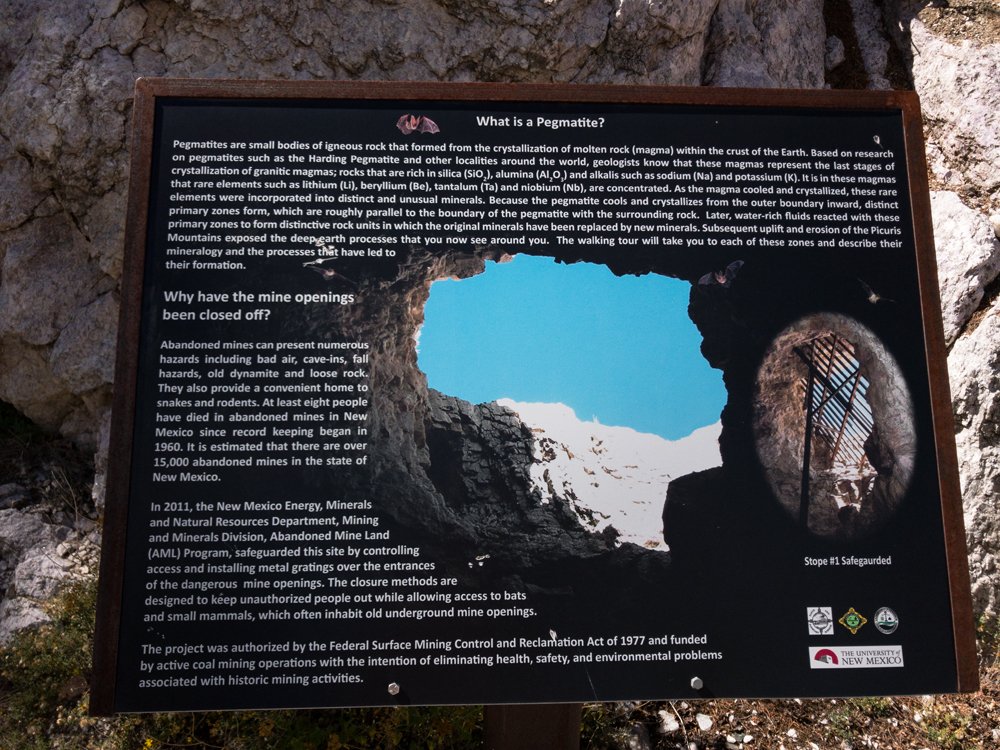

-The Mogollon-Datil Province

Experts think the Mogollon were an ancient Indian tribe inhabiting what is now eastern Arizona and western New Mexico. The area is geologically complex. Within the province is the Mogollon-Datil Volcanic Field. Numerous calderas populate the area, especially in the Gila Wilderness. The Mogollon Mountains rise to 11,000 feet. The Continental Divide is represented, between the Gila and the Rio Grande Rivers.

(New Mexico’s Mogollon-Datil Province)

-The Southern High Plains or The Great Plains

The High Plains province covers New Mexico’s eastern quarter. Elevations reach 4,000 feet in this mesa-like area. The High Plains are a part of a larger plains system called the Great Plains, its reach described in the Colorado section. The High Plains includes part of the Permian Basin, which is fueling an oil and natural gas boom in this mostly flat grazing country. The Permian is located in the south-east corner of the state near the Texas border. The High Plains Province also hosts part of what is called the late Miocene-Pliocene Ogallala Formation. It is a major aquifer in the United States. Larger cities include Hobbs, Lovington, and Carlsbad.

(New Mexico’s Southern High Plains or Great Plains)

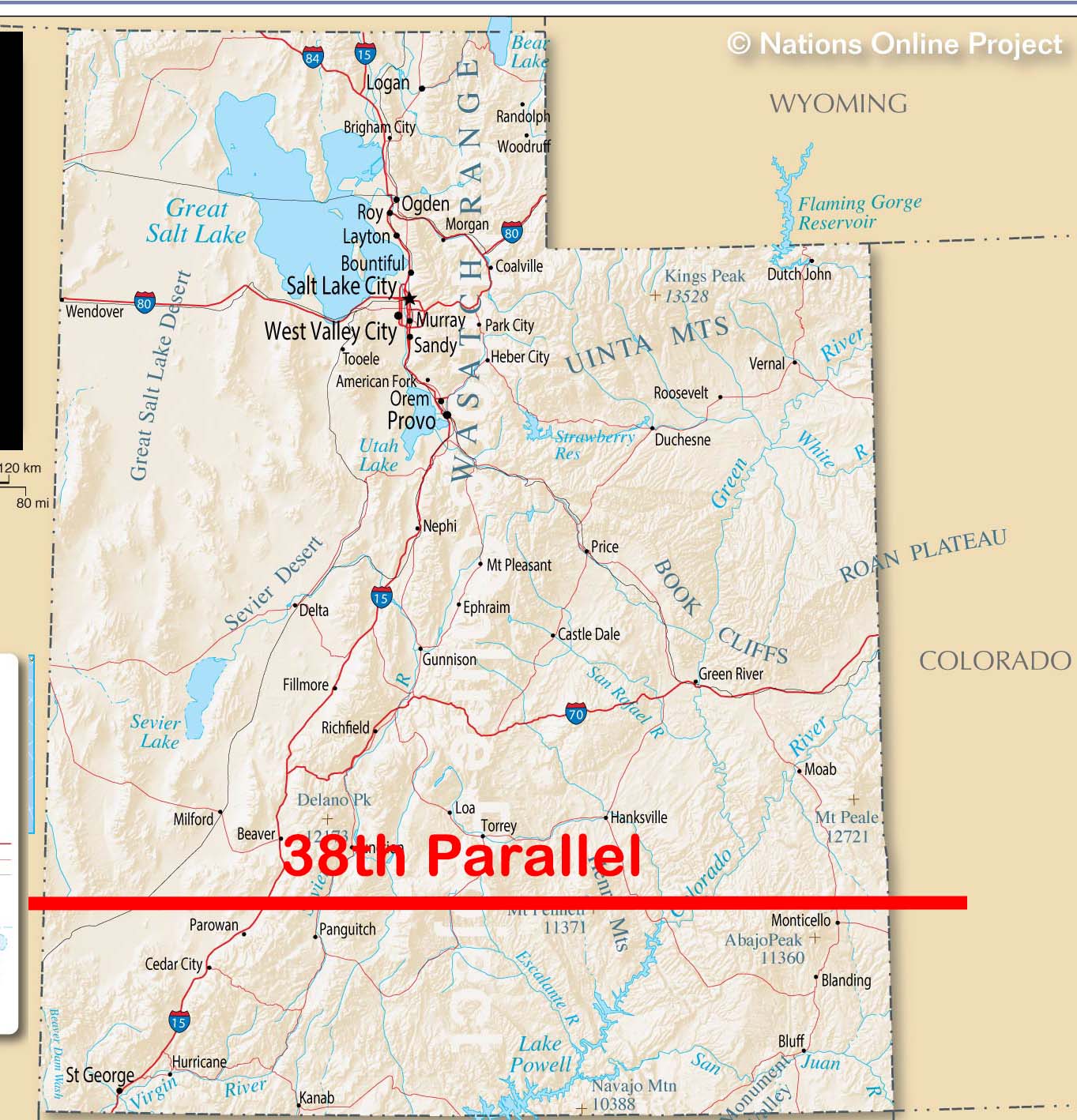

VII Southern Utah

-Introduction

Three major geologic provinces make up Utah. Basin and Range and the Colorado Plateau exist in Utah as they do in other states. The third is the Middle Rocky Mountains province which lies outside the Southwest. Some geologists also place a Transition Zone in Utah, which will be included for completeness.

-The Transition Zone

This Province is included as a Geologic Province of Utah by some and not by others. It is poorly defined, placed somewhere between Basin and Range to the West and the Colorado Plateau to the east. The largest city in the Zone and in Southern Utah is St. George, at an elevation of 2,860 and a population of 82,318. It is home to the St. George Dinosaur Discovery Site at Johnson Farm, a museum and locality that preserves a Jurassic era lake ecosystem. The next biggest town is Cedar City at 5,846 feet and a population of 31,223. This area is close to the Dixie National Forest. Within that forest, agate collecting goes on near Panguitch Lake.

Utah’s topography is mostly mountainous but varied. Almost 80 mountain ranges lie within or partially within it. The state’s highest point is 13,498-foot-high Kings Peak in the northern Uinta Mountains. Southern Utah mountain ranges climb to 8,600 feet or so.

-Basin and Range Province

Utah mountain ranges are typically 12 to 31 miles apart and 28 to 50 miles long. [“Physiographic Regions of Utah”

https://geology.utah.gov/popular/general-geology/utah-landforms/geologic-provinces/ Accessed 08/10/2023] Utah mean elevations reach 4,000 to 7,000 feet.

St. George and Cedar City both lie at the edge of Basin and Range, close to the poorly defined Transition Zone which separates Basin and Range from the Colorado Plateau. Viewed with Google Earth, Basin and Range levels off as it approaches the two cities. Proceeding east after that, the Colorado Plateau appears as a sparsely vegetated mesa.

-The Colorado Plateau

Southern Utah’s notable geologic features include plateaus, buttes, mesas, and deeply scored canyons. Utah’s lower southeast is the Four Corners area, distinguished by the Colorado Plateau. Monument Valley extends here into Utah from Arizona. Tribal land also exists on which no collecting is permitted without permission.

-The Colorado Plateau’s Great Basin Section

The Great Basin Section’s central feature is the Colorado River which eventually flows into Lake Mead near the Nevada border. The Green River makes up the Colorado’s principal tributary. Its drainage or watershed begins in northern Utah, northern Colorado, and southern Wyoming. Many cities in the arid Southwest, especially Las Vegas, Nevada, depends on water originating high in the Rocky Mountains.

(Utah, emphasizing Southern Utah)

(Southern Utah’s geologic provinces)